PC3-PSMA Cell Line: A High-Utility Model for PSMA-Directed Prostate Cancer Research

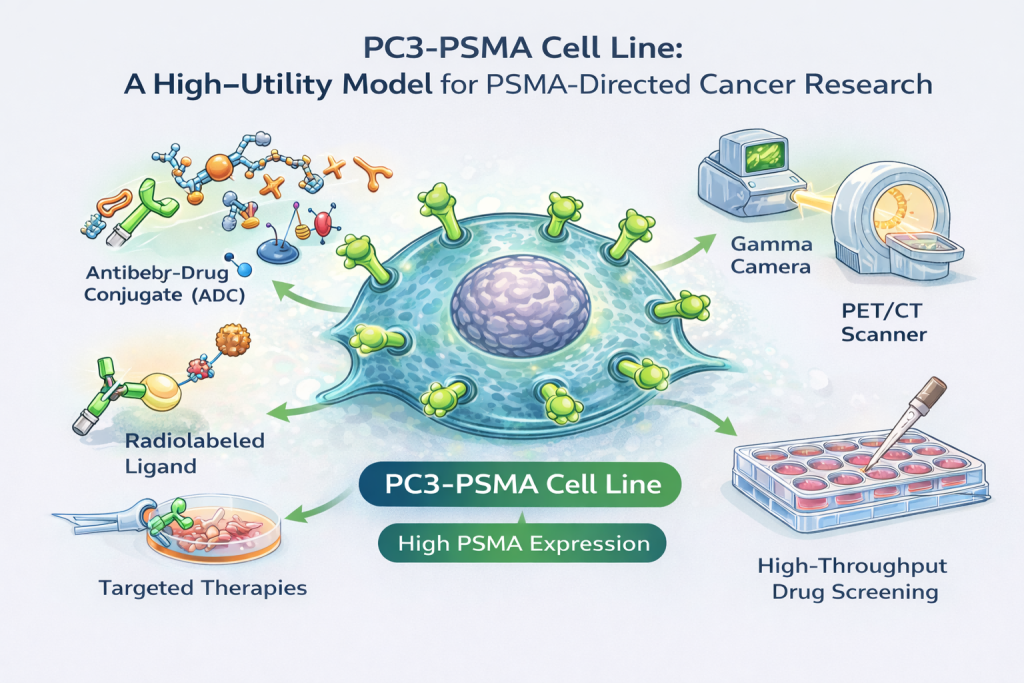

The PC3-PSMA cell line is a genetically engineered derivative of the PC3 prostate cancer model, stably expressing prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). This model has emerged as a robust platform for investigating PSMA biology, testing PSMA-targeted imaging agents, and evaluating novel therapeutic strategies.

PSMA Expression and Functional Characterization

PC3-PSMA cells exhibit high, stable expression of PSMA on the cell surface, making them ideal for preclinical studies that require consistent antigen levels. Recent research has utilized this model to:

Assess ligand binding and internalization of PSMA-targeted molecules

Evaluate radiotracer uptake for PET imaging applications

Test PSMA-directed therapies, including radioligand therapy and antibody-drug conjugates

Figure 1. PSMA expression in PC3-PSMA cells.

Translational Applications

The PC3-PSMA cell line serves as a versatile tool for preclinical evaluation:

- Radioligand Therapy: 177Lu-PSMA-617 and novel alpha-emitting ligands show specific uptake and cytotoxicity in PC3-PSMA cells.

- Immunotherapy Testing: CAR-T and bispecific antibodies targeting PSMA demonstrate selective cytotoxicity in co-culture assays.

- Drug Discovery: PSMA overexpression allows high-throughput screening of small molecules or antibody conjugates.

Recent studies using PC3-PSMA models have highlighted:

The impact of PSMA density on radiotracer uptake, informing clinical imaging strategies.

Synergistic effects when combining PSMA-targeted therapy with DNA damage repair inhibitors.

The utility of PC3-PSMA in evaluating tumor microenvironment interactions under therapeutic pressure.

These findings reinforce the PC3-PSMA line as an essential tool for translational prostate cancer research.

Conclusion

The PC3-PSMA cell line is a well-characterized, reproducible platform for studying PSMA-targeted diagnostics and therapeutics. By bridging molecular characterization, imaging, and preclinical therapeutic testing, it continues to facilitate the development of precision oncology strategies in prostate cancer.